Dirt & Bones: Words, Words, Words

My current manuscript (the first book of the BONE FIRE Duet) is set more than 7,000 years ago in the Wallachian Plains of Eastern Europe (now part of Romania). My main male character is Jorn the Word Singer. One of the primary decisions I had to make as I wrote about Jorn involved the words and phrases Jorn would use as his speech patterns and to convey his thoughts and view of the world.

Jorn is not only a “Word Singer” (bard) but also a warrior. He’s tough. He doesn’t hesitate to fight to get what he wants. Most of the time, in the portions of the novel told from Jorn’s point-of-view, I chose to use short phrases and also short words — “run” instead of “scamper”, “spoke” instead of “elaborated.” Of course, the kicker is that Jorn is also a bard. He composes and recites poetry to commemorate important events, to celebrate warriors, and to help his people remember their history, genealogy, and moral codes.

Jorn’s dual status as warrior and Word Singer gave me a “voice” conflict. Jorn speaks in short, tough sentences, but he’s a poet. The good news for me was that Jorn speaks an ancient language that linguists have been able to partially reconstruct — Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

Today, nearly all major European languages, plus some Middle Eastern and some Western Asian languages are descended from PIE. Fifty percent of people alive on earth speak a daughter language of PIE. If you speak English, or almost any other major European language, you’re one of the 50%.

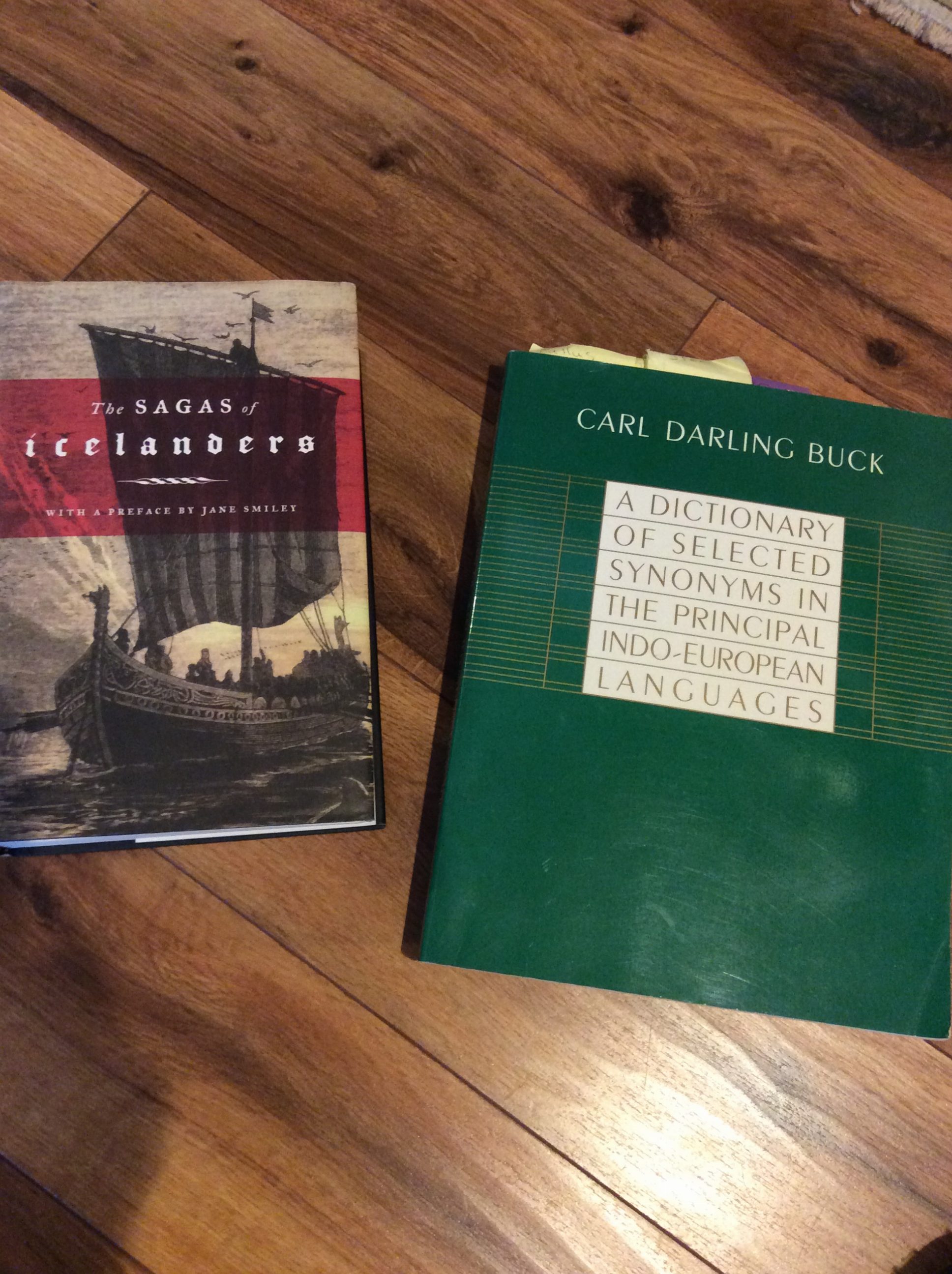

The green book on the left in the photo above — A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principal Indo-European Languages — has proven to be an invaluable research tool for me. For more than ten years, I’ve studied the contents of that green book, tracing synonyms and PIE root words. Thus, I’ve begun to learn a bit about how Jorn’s people thought. When you write novels set in ancient times, anything that gets you into the heads of the ancient people you write about is an amazing resource.

For example, when I read the many synonyms for the word “dog,” I realized that in almost all the daughter languages, those words are NOT related to one another. So I knew that dogs were named long before the PIE speakers swept through Europe, impacting indigenous cultures with their language and their DNA. That taught me two things 1) dogs had been domesticated for a long time prior to 6,000 B.C. and 2) they were so important to the ancient people of Europe that, when they were conquered and/or intermarried with PIE speakers, they still clung to their old words for that very special companion animal. That’s just one of the many gems I was able to glean from the green book.

Let’s look at the other book in the photo, The Sagas of the Icelanders. The Icelanders are one of the descendant peoples of those ancient Proto-Indo-European speakers, and one of the peoples who speak a descendant language — Icelandic. Their sagas comprise some of the oldest known literature in a PIE-descendant language. As I was developing Jorn’s voice, I read and read and read these translated sagas, which implanted a speech rhythm in my head. I decided to employ one of the Icelandic (and indeed, Scandinavian) literary devises to add word-music to Jorn’s voice.

That device is kenning. Kenning is a type of metaphor in which something is described by calling it something it is not. For example, a lazy boy might be called a coal-biter, because he prefers staying warm by the coals of the hearth rather than going out to fight or fish or hunt.

Also at the end of each Jorn chapter in the novel, I appended a short “poem” comprised of three lines, each line of a prescribed syllabic length: the first line, 2 syllables; the second 4; the third 8.

An example? After Jorn is attacked by a pack of wild dogs, that chapter ends with this paragraph and “word song.”

Jorn fell toward black unknowing sleep. His father called his name, voice broken. Jorn tried to tell him, tried to tell him–

Sing me

Songs of Word Fame.

Let me join the brave ghost warriors.

So there you have a small example of how language studies help a novelist develop a voice for a protagonist!

Which PIE daughter language(s) do you speak? Here are a few to choose from: English, Spanish, Romanian, Swedish, Dutch, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Flemish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Greek, any of the Gaelic languages… For me — English and a bit of conversational German!